Lung cancer

Overview

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers in many part of the world. It’s caused by harmful cells in your lungs growing unchecked. Treatments include surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation and targeted drugs. Screening is recommended if you’re at high risk. Advances in treatments have caused a significant decline in lung cancer deaths in recent years.

What is lung cancer?

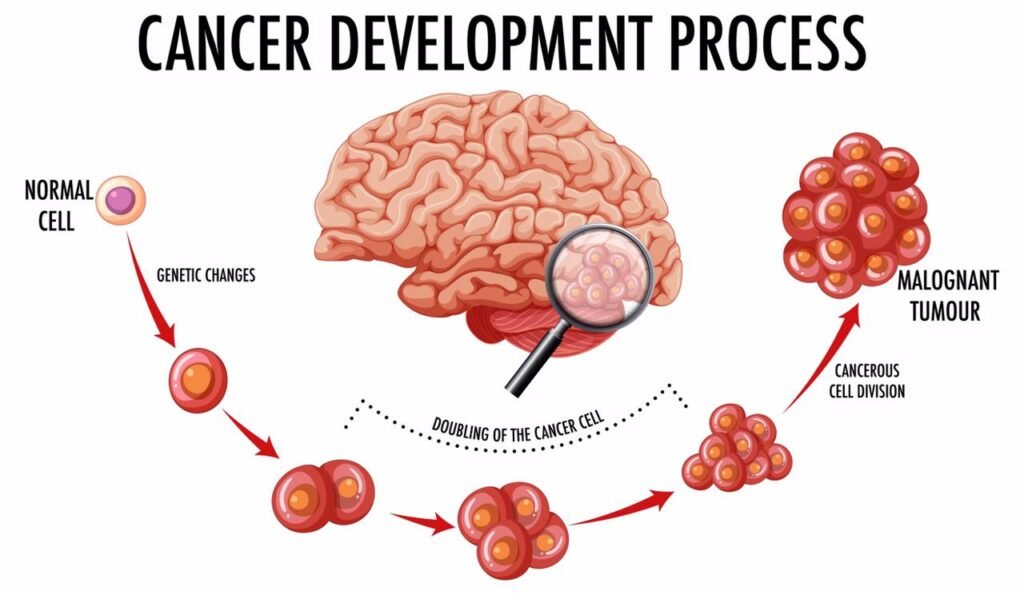

Lung cancer is a disease caused by uncontrolled cell division in your lungs. Your cells divide and make more copies of themselves as a part of their normal function. But sometimes, they get changes (mutations) that cause them to keep making more of themselves when they shouldn’t. Damaged cells dividing uncontrollably create masses, or tumors of tissue that eventually keep your organs from working properly.

Lung cancer is the name for cancers that start in your lungs — usually in the airways bronchi or bronchioles) or small air sacs (alveoli). Cancers that start in other places and move to your lungs are usually named for where they start (your healthcare provider may refer to this as cancer that’s metastatic to your lungs).

Types of lung cancer

There are many cancers that affect the lungs, but we usually use the term “lung cancer” for two main kinds: non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer.

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer. It accounts for over 80% of lung cancer cases. Common types include adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Adenosquamous carcinoma and sarcomatoid carcinoma are two less common types of NSCLC.

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC)

Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) grows more quickly and is harder to treat than NSCLC. It’s often found as a relatively small lung tumor that’s already spread to other parts of your body. Specific types of SCLC include small cell carcinoma (also called oat cell carcinoma) and combined small cell carcinoma.

Other types of cancer in the lungs

Other types of cancer can start in or around your lungs, including lymphomas (cancer in your lymph nodes), sarcomas (cancer in your bones or soft tissue) and pleual mesothelioma (cancer in the lining of your lungs). These are treated differently and usually aren’t referred to as lung cancer.

Stages of lung cancer

Cancer is usually staged based on the size of the initial tumor, how far or deep into the surrounding tissue it goes, and whether it’s spread to lymph nodes or other organs. Each type of cancer has its own guidelines for staging.

Each stage has several combinations of size and spread that can fall into that category. For instance, the primary tumor in a Stage III cancer could be smaller than in a Stage II cancer, but other factors put it at a more advanced stage. The general staging for lung cancer is:

- Stage 0 (in-situ):Cancer is in the top lining of the lung or bronchus. It hasn’t spread to other parts of the lung or outside of the lung.

- Stage I:Cancer hasn’t spread outside the lung.

- Stage II:Cancer is larger than Stage I, has spread to lymph nodes inside the lung, or there’s more than one tumor in the same lobe of the lung.

- Stage III:Cancer is larger than Stage II, has spread to nearby lymph nodes or structures or there’s more than one tumor in a different lobe of the same lung.

- Stage IV:Cancer has spread to the other lung, the fluid around the lung, the fluid around the heart or distant organs.

Limited vs. extensive stage

While providers now use stages I through IV for small cell lung cancer, you might also hear it described as limited or extensive stage. This is based on whether the area can be treated with a single radiation field.

- Limited stage SCLCis confined to one lung and can sometimes be in the lymph nodes in the middle of the chest or above the collar bone on the same side.

- Extensive stage SCLCis widespread throughout one lung or has spread to the other lung, lymph nodes on the opposite side of the lung, or to other parts of the body.

Metastatic lung cancer

Metastatic lung cancer is cancer that starts in one lung but spreads to the other lung or to other organs. Metastatic lung cancer is harder to treat than cancer that hasn’t spread outside of its original location.

Symptoms of lung cancer

Most lung cancer symptoms look similar to other, less serious illnesses. Many people don’t have symptoms until the disease is advanced, but some people have symptoms in the early stages. For those who do experience symptoms, it may only be one or a few of these:

- A cough that doesn’t go away or gets worse over time.

- Trouble breathing or shorness of breath (dyspnea).

- Chest pain or discomfort.

- Coughing up blood (hemoptysis).

- Loss of appetite.

- Unexpained weight loss.

- Unexplained fatugue (tiredness).

- Shoulder pain.

- Swelling in the face, neck, arms or upper chest (superior vena cava syndrome).

- Small pupil and drooping eyelid in one eye with little or no sweating on that side of your face (Horner’s syndrome).

What are the first signs of lung cancer?

A cough or pneumonia that keeps coming back after treatment can sometimes be an early sign of lung cancer (though it can also be a sign of less serious conditions). The most common signs of lung cancer include a persistent or worsening cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, hoarseness or unexplained weight loss.

Depending on where in your lungs cancer starts, some of these symptoms can happen early (in stages I or II) but often they don’t happen until cancer has progressed to later stages. That’s why it’s important to get screened for lung cancer if you’re at higher risk.

Risk factors for lung cancer

While there are many factors that can increase your risk of lung cancer, smoking any kind of tobacco products, including cigarettes, cigars or pipes is the biggest single risk factor. Experts estimate that 80% of lung cancer deaths are smoking-related.

Other risk factors include:

- Being exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke.

- Being exposed to harmful substances, like air pollution, radon, asbestos, uranium, diesel exhaust, silica, coal products and others.

- Having previous radiation treatments to your chest (for instance, for breast cancer or lymphoma).

- Having a family history of lung cancer.

How is lung cancer diagnosed?

Diagnosing lung cancer can be a multi-step process. Your first visit to a healthcare provider will usually involve them listening to your symptoms, asking you about your health history and performing a physical exam (like listening to your heart and lungs). Since lung cancer symptoms are similar to many other, more common illnesses, you provider may start by getting blood tests and a chest X-ray.

If your provider suspects you could have lung cancer, your next steps in diagnosis would usually involve more imaging tests, like a CT scan, and then a biopsy. Other tests include using a PET/CT scan to see if cancer has spread, and tests of cancerous tissue from a biopsy to help determine the best kind of treatment.

Medications/treatments for lung cancer

Lung cancer treatments include surgery, radiofrequency ablation, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, targeted drug therapy and immunotherapy.

Surgery

NSCLC that hasn’t spread and SCLC that’s limited to a single tumor can be eligible for surgery. Your surgeon might remove the tumor and a small amount of healthy tissue around it to make sure they don’t leave any cancer cells behind. Sometimes they have to remove all or part of your lung (resection) for the best chance that the cancer won’t come back.

Radiofrequency ablation

NSCLC tumors near the outer edges of your lungs are sometimes treated with radiofrequency ablation (RFA). RFA uses high-energy radio waves to heat and destroy cancer cells.

Radiation therapy

Radiation uses high energy beams to kill cancer cells. It can be used by itself or to help make surgery more effective. Radiation can also be used as palliative care, to shrink tumors and relieve pain. It’s used in both NSCLC and SCLC.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often a combination of multiple medications designed to stop cancer cells from growing. It can be given before or after surgery or in combination with other types of medication, like immunotherapy. Chemotherapy for lung cancer is usually given through an IV.

Targeted drug therapy

In some people with NSCLC, lung cancer cells have specific changes (mutations) that help the cancer grow. Special drugs target these mutations to try to slow down or destroy cancer cells. Other drugs, called angiogenesis inhibitors, can keep the tumor from creating new blood vessels, which the cancer cells need to grow.

Immunotherapy

Our bodies usually recognize cells that are damaged or harmful and destroy them. Cancer has ways to hide from the immune system to keep from being destroyed. Immunotherapy reveals cancer cells to your immune system so your own body can fight cancer.

Treatments to ease symptoms (palliative care)

Some lung cancer treatments are used to relieve symptoms, like pain and difficulty breathing. These include therapies to reduce or remove tumors that are blocking airways, and procedures to remove fluid from around your lungs and keep it from coming back.

How can I prevent lung cancer?

Since we don’t know what causes most cancers for sure, the only preventative measures are focused on reducing your risk. Some ways to reduce your risk include:

- Don’t smoke or quit smoking if you do. Your risk of lung cancer starts coming down within five years of quitting.

- Avoid second hand smoke and other substances that can harm your lungs.

- Eat a healthy diet and maintain a weight that’s healthy for you. Some studies suggest that eating fruits and vegetables (two to six-and-a-half cups per day) can help reduce your risk of cancer.

- Get screened for lung cancer if you’re at high risk.

Lung cancer screening

You can increase your chances of catching cancer in its earliest stages with sccreening tests. You’re eligible for lung cancer screening if you meet all of these requirements:

- You’re between the ages of 50 and 80.

- You either currently smoke or have quit smoking within the last 15 years.

- You have a 20 pack-year smoking history (number of packs of cigarettes per day times the number of years you smoked).

Ask your healthcare provider about the benefits and risks of yearly screening.

Survival rate of lung cancer

The survival rate of lung cancer depends greatly on how far cancer has spread when it’s diagnosed, how it responds to treatment, your overall health and other factors. For instance, for small tumors that haven’t spread to the lymph nodes, the survival rates are 90% for tumors that are smaller than 1 cm, 85% for tumors between 1 and 2 cm, and 80% for tumors between 2 and 3 cm.

The relative five-year survival rate for lung cancer diagnosed at any stage is 22.9%. The five-year relative survival rates by how much cancer has spread is:

- 2% (64% for NSCLC, 29% for SCLC) for cancer that’s confined to one lung (localized).

- 5% (37% for NSCLC, 18% for SCLC) for cancer that’s spread to the lymph nodes (regional).

- 7% (26% for NSCLC, 3% for SCLC) for cancer that’s spread to other organs (distant).

Remember that these numbers don’t take into account the specific details of your diagnosis and treatment. Thanks to improvements in detection and treatment, the rates of lung cancer deaths have been rapidly coming down in recent years.

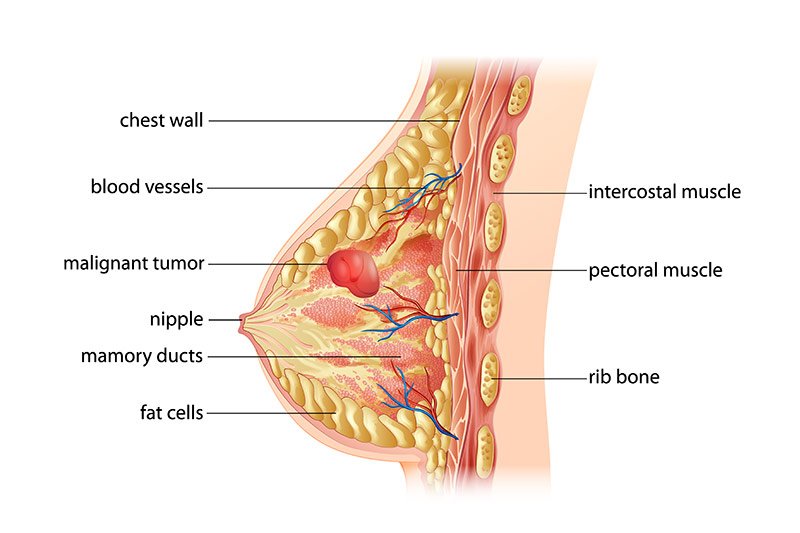

Breast cancer

Overview

Breast cancer is when breast cells mutate and become cancerous cells that multiply and form tumors. Breast cancer typically affects women and people assigned female at birth (AFAB) age 50 and older, but it can also affect men and people assigned male at birth (AMAB), as well as younger women. Healthcare providers may treat breast cancer with surgery to remove tumors or treatment to kill cancerous cells.ars.

What is breast cancer?

Breast cancer is when breast cells mutate and become cancerous cells that multiply and form tumors. Breast cancer typically affects women and people assigned female at birth (AFAB) age 50 and older, but it can also affect men and people assigned male at birth (AMAB), as well as younger women. Healthcare providers may treat breast cancer with surgery to remove tumors or treatment to kill cancerous cells.

About 80% of breast cancer cases are invasive, meaning a tumor may spread from your breast to other areas of your body.

Types of breast cancer

Healthcare providers determine cancer types and subtypes so they can tailor treatment to be as effective as possible with the fewest possible side effects. Common types of breast cancer include:

• Invasive(infiltrating) ductal carcinoma(IDC): This cancer starts in your milk ducts and spreads to nearby breast tissue. It’s the most common type of breast cancer.

• Lobular breast cancer: This breast cancer starts in the milk-producing glands (lobules) in your breast and often spreads to nearby breast tissue. It’s the second most common breast cancer in the United States.

• Dectal carcenoma in situ (DCIS): Like IDC, this breast cancer starts in your milk ducts. The difference is DCIS doesn’t spread beyond your milk ducts.

Less common breast cancer types include:

• Triple-negetive breast cancer (TNBC): This invasive cancer is aggressive and spreads more quickly than other breast cancers.

• Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC): This rare, fast-growing cancer looks like a rash on your breast.

• Paget’s disease of the breast: This rare cancer affects the skin of your nipple and may look like a rash. Less than 4% of all breast cancers are Paget’s disease of the breast.

Breast cancer subtypes

Healthcare providers classify breast cancer subtypes by receptor cell status. Receptors are protein molecules in or on cells’ surfaces. They can attract or attach to certain substances in your blood, including hormones like estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen and progesterone help cancerous cells to grow. Finding out if cancerous cells have estrogen or progesterone receptors helps healthcare providers plan breast cancer treatment.

Types of breast cancer

Healthcare providers determine cancer types and subtypes so they can tailor treatment to be as effective as possible with the fewest possible side effects. Common types of breast cancer include:

• Invasive(infiltrating) ductal carcinoma(IDC): This cancer starts in your milk ducts and spreads to nearby breast tissue. It’s the most common type of breast cancer.

• Lobular breast cancer: This breast cancer starts in the milk-producing glands (lobules) in your breast and often spreads to nearby breast tissue. It’s the second most common breast cancer in the United States.

• Dectal carcenoma in situ (DCIS): Like IDC, this breast cancer starts in your milk ducts. The difference is DCIS doesn’t spread beyond your milk ducts.

Less common breast cancer types include:

• Triple-negetive breast cancer (TNBC): This invasive cancer is aggressive and spreads more quickly than other breast cancers.

• Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC): This rare, fast-growing cancer looks like a rash on your breast.

• Paget’s disease of the breast: This rare cancer affects the skin of your nipple and may look like a rash. Less than 4% of all breast cancers are Paget’s disease of the breast.

Breast cancer subtypes

Healthcare providers classify breast cancer subtypes by receptor cell status. Receptors are protein molecules in or on cells’ surfaces. They can attract or attach to certain substances in your blood, including hormones like estrogen and progesterone. Estrogen and progesterone help cancerous cells to grow. Finding out if cancerous cells have estrogen or progesterone receptors helps healthcare providers plan breast cancer treatment.

Subtypes include:

- ER-positive (ER+) breast cancers have estrogen receptors.

- PR-positive (PR+)breast cancers have progesterone receptors.

- HR-positive (HR+)breast cancers have estrogen and progesterone receptors.

- HR-negative (HR-)breast cancers don’t have estrogen or progesterone receptors.

- HER2-positive (HER2+)breast cancers, which have higher than normal levels of the HER2 protein. This protein helps cancer cells to grow. About 15% to 20% of all breast cancers are HER2-positive.

Symptoms of breast cancer

The condition can affect your breasts in different ways. Some breast cancer symptoms are very distinctive. Others may simply seem like areas of your breast that look very different from any other area. Breast cancer may not cause noticeable symptoms either. But when it does, symptoms may include:

- A change in the size, shape or contour of your breast.

- A mass or lump, which may feel as small as a pea.

- A lump or thickening in or near your breast or in your underarm that persists through your mentrual cycle.

- A change in the look or feel of your skin on your breast or nipple. Your skin may look dimpled, puckered, scaly or inflamed. It may look red, purple or darker than other parts of your breast.

- A marble-like hardened area under your skin.

- A blood-stained or clear fluid distarge from your nipple.

What causes breast cancer?

Experts know breast cancer happens when breast cells mutate and become cancerous cells that divide and multiply to create tumors. They aren’t sure what triggers that change. However, research shows there are several risk factors that may increase your chances of developing breast cancer. These include:

- Age: Being 55 or older.

- Sex: Women and people AFAB are much more likely to develop the condition than men and people AMAB.

- Family history: If your parents, siblings, children or other close relatives have breast cancer, you’re at risk of developing the disease.

- Genetics: Up to 15% of people with breast cancer develop the disease because they have inherited genetic mutations. The most common genetic mutations involve the BRCA1and BRCA2 genes.

- Smoking: Tobacco use has been linked to many different types of cancer, including breast cancer.

- Drinking beverages containing alcohol: Research shows that drinking beverages containing alcohol may increase breast cancer risk.

- Having obesity.

- Radiation exposure: If you’ve had prior radiation therapy — especially to your head, neck or chest — you’re more likely to develop breast cancer.

- Hormone replacement therapy: People who use hormone replacement therapy(HRT) have a higher risk of being diagnosed with the condition.

Diagnosis of breast cancer

Healthcare providers may do physical examinations or order mamograms to check for signs of breast cancer. But they do the following tests to diagnose the disease:

- Breast ultrasoung.

- Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

- Breast biopsy.

- Immunohistochemistry test to check for hormone receptors.

- Genetic tests to identify mutations that cause breast cancer.

Stages of breast cancer

Healthcare providers use cancer staging systems to plan treatment. Staging cancer also helps providers set a prognosis, or what you can expect after treatment. Breast cancer staging depends on factors like breast cancer type, tumor size and location, and whether cancer has spread to other areas of your body. Breast cancer stages are:

- Stage 0: The disease is noninvasive, meaning it hasn’t spread from your breast ducts to other parts of your breast.

- Stage I: There are cancerous cells in nearby breast tissue.

- Stage II: The cancerous cells have formed a tumor or tumors. The tumor is either smaller than 2 centimeters across and has spread to underarm lymph nodes or larger than 5 centimeters across but hasn’t spread to underarm lymph nodes. Tumors at this stage can measure anywhere between 2 and 5 centimeters across, and may or may not affect the nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage III: There’s breast cancer in nearby tissue and lymph nodes. Stage III is usually referred to as locally advanced breast cancer.

- Stage IV: Cancer has spread from your breast to areas like your bones, liver, lungs or brain.

Treatement of breast cancer

Surgery is the primary breast cancer treatment, but healthcare providers may use other treatments. Breast cancer surgeries include:

- Mastectomy

- Lumpectomy

- Breast reconstruction.

Healthcare providers may combine surgery with one or more of the following treatments:

- Chmotherapy

- Radiation therapy, including intraoperative radiation therapy (IOTR).

- Immunotherapy.

- Hormone therapy, including selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) therapy.

- Targeted therapy.

What’s the outlook for breast cancer?

Right now, more people are being diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer — meaning they’re diagnosed when it’s easier to treat — and fewer people are dying of breast cancer.

Data shows 99% of people with early-stage breast cancer were alive five years after diagnosis. In some cases, they may be considered cured of breast cancer. But breast cancer can come back, and when it does, it may come back as metastatic breast cancer.

Outlook may also depend on race. According to the American Cancer Society, Black women and people AFAB are slightly less likely to develop breast cancer than white women. But Black women are more likely to die of breast cancer than white women.

Colorectal (Colon) Cancer

Overview

Colon cancer develops from polyps (growths) in your colon’s inner lining. Healthcare providers have screening tests and treatments that detect and remove precancerous polyps. If untreated, colon cancer may spread to other areas of your body. Thanks to these tests, early treatment and new kinds of treatment, fewer people are dying from colon cancer.

What is colon cancer?

Colon (colorectal) cancer starts in your colon (large intestine), the long tube that helps carry digested food to your rectum and out of your body.

Colon cancer develops from certain polyps or growths in the inner lining of your colon. Healthcare providers have screening tests that detect precancerous polyps before they can become cancerous tumors. Colon cancer that’s not detected or treated may spread to other areas of your body. Thanks to screening tests, early treatment and new kinds of treatment, fewer people are dying from colon cancer.

How does this condition affect people?

Your colon wall is made of layers of mucous membrane, tissue and muscle. Colon cancer starts in your mucosa, the innermost lining of your colon. It consists of cells that make and release mucus and other fluids. If these cells mutate or change, they may create a colon polyp.

Over time, colon polyps may become cancerous. (It usually takes about 10 years for cancer to form in a colon polyp.) Left undetected and/or untreated, the cancer works its way through a layer of tissue, muscle and the outer layer of your colon. The colon cancer may also spread to other parts of your body via your lymph nodes or your blood vessels.

Symptoms of colon cancer

You can have colon cancer without having symptoms. If you do have symptoms, you may not be sure if changes in your body are signs of colon cancer. That’s because some colon cancer symptoms are similar to symptoms of less serious conditions. Common symptoms of colon cancer include:

• Blood on or in your stool (poop): Talk to a healthcare provider if you notice blood in the toilet after you poop or after wiping, or if your poop looks dark or bright red. It’s important to remember blood in poop doesn’t mean you have colon cancer. Other things — from hemorrhoids to anal tears to eating beets — may change your poop’s appearance. But it’s always better to check with a healthcare provider any time you notice blood in or on your stool.

• Persistent changes in your bowel habits (how you poop): Talk to a healthcare provider if you have persistent constipation and/or diarrhea, or if you feel as if you still need to poop after going to the bathroom.

• Abdominal (belly) pain: Talk to a healthcare provider if you have belly pain with no known cause, that doesn’t go away or hurts a lot. Many things may cause belly pain, but it’s always best to check with a healthcare provider if you have unusual or frequent belly pain.

• Bloated stomach: Like belly pain, there are many things that may make you feel bloated. Talk to a healthcare provider if your bloated belly lasts for more than a week, gets worse or you have other symptoms like vomiting or blood in or on your poop.

• Unexplained weight loss: This is a noticeable drop in your body weight when you’re not trying to lose weight.

• Vomiting: Talk to a healthcare provider if you’ve been vomiting periodically for no known reason or if you vomit a lot in 24 hours.

• Fatigue and feeling short of breath: These are symptoms of anemia. Anemia may be a sign of colon cancer.

What causes colon cancer?

Like all types of cancer, colon cancer happens when cells grow and divide uncontrollably. All cells in your body are constantly growing, dividing and dying. That’s how your body remains healthy and working as it should. In colon cancer, cells lining your colon and rectum keep growing and dividing even when they’re supposed to die. These cancerous cells may come from polyps in your colon.

Medical researchers aren’t sure why some people develop precancerous colon polyps that become colon cancer. They do know certain risk factors increase people’s chances of developing precancerous polyps and colon cancer.

Those risk factors include certain medical conditions, including inherited conditions, and lifestyle choices. Having one or more risk factors for colon cancer doesn’t mean you’ll develop the condition. It just means you have increased risk. Understanding risk factors may help you decide if you should talk to a healthcare provider about your risk of developing colon (colorectal) cancer.

Lifestyle choices that are risk factors for colon cancer

- Smoking:Using tobacco products, including chewing tobacco and e-cigarettes, increases your risk of developing colon cancer.

- Excessive alcohol use:In general, men and people AMAB should limit beverages containing alcohol to two servings a day. Women and people AFAB should limit beverages containing alcohol to one serving a day. Even light alcohol use can increase your risk of developing cancer.

- Having obesity:Eating high-fat, high-calorie foods may affect your weight and increase your risk of colon cancer.

- Having a diet that includes lots of red meat and processed meat:Processed meat includes bacon sausage and lunchmeat. Healthcare providers recommend you limit red meat and processed meat to two servings a week.

- Not exercising:Any kind of physical activity may reduce your risk of developing colon cancer.

Medical conditions that increase colon cancer risk

- Inflommatory bowel disease:People who have conditions like chronic ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s colitis, which cause inflammation in their colon lining, may have an increased risk of colon cancer. The risk increases if you have inflammatory bowel disease that lasts more than seven years and affects large parts of your colon.

- Inherited conditions:Certain conditions like Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis may increase your risk of developing colon cancer. Colon cancer may happen if you inherit a gene that causes cancer.

- A family history of colon and other kinds of cancer:If a close family member has colon cancer, you may have an increased risk of developing the condition. Close family members include your biological parents, siblings and children. Your risk may be higher if any biological family member developed colon cancer before age 45.

- A family history of polyps:If your parent, sibling or child has an advanced polyp, you may have an increased risk of getting colon cancer. An advanced polyp may be a large polyp. Medical pathologists may characterize a polyp as being advanced if they see certain changes in the polyp when they look at it under a microscope that are signs the polyp may contain cancerous cells.

- Many polyps:People with numerous colon polyps — including adenomas, serrated polyps or other types of polyps — often have an increased risk of developing polyps and colon cancer. People may inherit a tendency toward having many colon polyps.

Diagnose colon cancer

Healthcare providers use several tests to diagnose colon cancer. Those tests include:

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Comrehensive metabolic panel (CMP).

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay: Cancer cells and normal cells release CEA into your bloodstream. High CEA levels may be a sign of colon cancer.

- X-rays.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

- Position emission tomography (PET) scan.

- Ultrasound.

- Biopsy.

Stage colon cancer

There are five stages of colon cancer. Three of the four stages have three sub-stages. The colon cancer staging system includes the following:

Stage 0: Healthcare providers may refer to this as carcinoma in situ. When they do, they’re talking about abnormal or precancerous cells in your mucosa, the innermost layer of your colon wall.

Stage I: Stage I colorectal cancer has grown into the wall of your intestine but hasn’t spread beyond the muscular coat or into close lymph nodes.

Stage II: The cancer has spread farther into the wall of your intestine but hasn’t spread to nearby lymph nodes. There are three types of Stage II colon cancer:

- Stage IIA:Cancer has spread through most of your colon wall but hasn’t grown into the wall’s outer layer.

- Stage IIB:Cancer has spread into the outer layer of your colon wall or through the wall.

- Stage IIC:Cancer has spread to a nearby organ.

Stage III: In this stage, colon cancer has spread to your lymph nodes. Like Stage II colon cancer, there are three sub-stages of Stage III colon cancer:

- Stage IIIA:There’s cancer in the first or second layers of your colon wall and it’s spread to one to four lymph nodes.

- Stage IIIB:The cancer affects more layers of your colon wall but only affects one to three lymph nodes. Cancer that affects fewer colon wall layers but has spread to four or more lymph nodes is also a stage IIIB colon cancer.

- Stage IIIC:There’s cancer in the outer layer or the next outermost layer of your colon and in four or more lymph nodes. Cancer that’s spread into a nearby organ and one or more lymph nodes is also a stage IIIC colon cancer.

Stage IV: Cancer has spread (metastasized) to other areas of your body, such as your liver, lungs or ovaries:

- Stage IVA:In this stage, cancer has spread to one organ or to lymph nodes that are farther or more distant from your colon.

- Stage IVB:The cancer has moved to more than one distant organ and more lymph nodes.

- Stage IVC:Cancer affects distant organs, lymph nodes and abdominal tissue.

Treatment of colon cancer

Surgery is the most common colon cancer treatment. There are different colon cancer surgeries and procedures:

- Polypectomy:This surgery removes cancerous polyps.

- Partial colectomy:This is also called colon resection surgery. Surgeons remove the section of your colon that contains a tumor and some surrounding healthy tissue. They’ll reconnect healthy colon sections in a procedure called anastomosis.

- Surgical resection with colostomy:Like a colectomy, surgeons remove the section of your colon that contains a tumor. In this surgery, however, they can’t connect healthy colon sections. Instead, they do a colostomy. In a colostomy, your bowel is moved to an opening in your abdominal wall so your poop is collected in a bag.

- Radiofrequency ablation:This procedure uses heat to destroy cancer cells.

Healthcare providers may combine surgery with adjuvant therapy. This is cancer treatment done before or after surgery. They may also use these treatments for colon cancer that has spread or come back. Treatments may include:

- Chemotherapy:Healthcare providers may use chemotherapy drugs to shrink tumors and ease colon cancer symptoms.

- Targeted therapy:This treatment targets the genes, proteins and tissues that help colon cancer cells grow and multiply. Healthcare providers often use a type of targeted therapy called monoclonal antibody therapy. This therapy uses lab-created antibodies that attach to specific targets on cancer cells or cells that help cancer cells grow. The antibodies kill the cancer cells.

Can colon cancer be prevented?

You may not be able to prevent colon cancer, but you can reduce your risk of developing the condition by managing risk factors:

- Avoid tobacco. If you smoke and want help quitting, talk to a healthcare provider about smoking cessation programs.

- Use moderation when you drink beverages containing alcohol.

- Maintain a healthy weight.

- Eat a healthy diet. Add fruit and vegetables to your diet and cut back on red meat processed foods, and high-fat and high-calorie foods. Drinking coffee may lower your risk of developing colon cancer.

- Keep track of your family medical history.Colon cancer can run in families. Tell your healthcare provider if your biological parents, siblings or children have colon cancer or an advanced polyp or if any of your family has cancer before age 45.

- Follow colon cancer screening guidelines. Ask your healthcare provider when you should have colon cancer screening. If you have chronic irritable bowel disease or a family history of colon cancer, your healthcare provider may recommend you start screening earlier than age 45.

What are the survival rates for colon cancer?

NCI data shows that overall, 65% of people with colorectal cancer were alive five years after diagnosis. (A survival rate is an estimate based on the experiences of people with specific kinds of cancer.

Colorectal cancer survival rates vary based on the cancer stage at diagnosis. For example, 73% of people with colorectal cancer that’s spread to nearby tissues, organs or lymph nodes were alive five years after diagnosis. That five-year survival rate drops to 17% if the cancer spreads to a distant organ or lymph node.

A survival rate is an estimate based on outcomes — how long people lived after treatment for a specific type of cancer. In this case, survival rates are based on the experiences of large groups of people who have colorectal cancer, and not just colon cancer. In addition, many things affect colon cancer survival rates. If you have this condition, your healthcare provider is your best resource for information about what you can expect.

Prostate Cancer

Overview

Prostate cancer develops in the prostate gland, a part of the reproductive system in men and people assigned male at birth. Many people choose active surveillance (no treatment) because prostate cancer tends to grow slowly and stay in the gland. For cancers that grow fast and spread, common treatments include radiation and surgery.

What is prostate cancer?

Prostate cancer develops in the prostate, a small walnut-shaped gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum in men and people assigned male at birth (AMAB). This tiny gland secretes fluid that mixes with semen, keeping sperm healthy for conception and pregnancy.

Prostate cancer is a serious disease. Fortunately, most people with prostate cancer get diagnosed before it spreads beyond their prostate gland. Treatment at this stage often eliminates the cancer.

Types of prostate cancer?

If you’re diagnosed with prostate cancer, it’s most likely an adenocarcinoma. Adenocarcinomas start in the cells of glands — like your prostate — that secrete fluid. Rarely, prostate cancer forms from other types of cells.

Less common types of prostate cancers include:

- Small cell carcinomas.

- Transitional cell carcinomas.

- Neuroendocrine tumers.

Symptoms of prostate cancer

Early-stage prostate cancer rarely causes symptoms. These issues may occur as the disease progresses:

- Frequent, sometimes urgent, need to pee, especially at night.

- Weak urine flow or flow that starts and stops.

- Pain or burning when you pee (dysuria).

- Loss of bladder control (urinary incontinence).

- Loss of bowel control (fecal incontinence).

- Painful ejaculation and erectile dysfunction (ED).

- Blood in semen (tospermia) or pee.

- Pain in your low back, hip or chest.

What causes prostate cancer?

Experts aren’t sure what causes cells in your prostate to become cancer cells. As with cancer in general, prostate cancer forms when cells divide faster than usual. While normal cells eventually die, cancer cells don’t. Instead, they multiply and grow into a lump called a tumor. As the cells continue to multiply, parts of the tumor can break off and spread to other parts of your body (metastasize).

Luckily, prostate cancer usually grows slowly. Most tumors are diagnosed before the cancer has spread beyond your prostate. Prostate cancer is highly treatable at this stage.

Risk factors for prostate cancer?

The most common risk factors include:

- Your risk increases as you get older. You’re more likely to get diagnosed if you’re over 50. About 60% of prostate cancers occur in people older than 65.

- Race and ethnicity.You’re at greater risk if you’re Black or of African ancestry. You’re more likely to develop prostate cancers that are more likely to spread. You’re also at greater risk of prostate cancer forming before age 50.

- Family history of prostate cancer.You’re two to three times more likely to get prostate cancer if a close family member has it.

- You’re at greater risk if you have Lynch syndrome or if you inherited mutated (changed) genes associated with increased breast cancer risk (BRCA1 and BRCA2).

Some studies have identified other prostate cancer risk factors, but the evidence is mixed. Other potential risk factors include:

- Smoking.

- Prostatitis.

- Having a BMI > 30 (having obesity).

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

How is prostate cancer diagnosed?

Screenings can help catch prostate cancer early. If you’re average risk, you’ll probably have your first screening test at age 55. You may need earlier screenings if you’re in a high-risk group. Screenings usually stop after age 70.

You may need additional tests or procedures if screenings show you may have prostate cancer.

Screening tests for prostate cancer

Screening tests can show whether you have signs of prostate cancer that require more testing:

- Digital rectal exam:Your provider inserts a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum and feels your prostate gland. Bumps or hard areas may mean cancer.

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test:The prostate gland makes a protein called protein-specific antigen (PSA). High PSA levels may indicate cancer. Levels also rise if you have benign conditions, such as BPH or prostatitis.

Diagnostic procedures for prostate cancer

Not everyone who likely has prostate cancer will need a definitive diagnosis. For example, if your provider thinks your tumor is growing slowly, they may delay more testing because it’s not serious enough to require treatment. If it’s more aggressive (growing fast or spreading), you may need additional tests, including a biopsy.

- Imaging:An MRI or a transrectal ultrasound can show images of your prostate gland, including suspicious areas that may be cancer. Imaging results can help your provider decide whether to perform a biopsy.

- Biopsy:During a needle biopsy, a healthcare provider removes a tissue sample for testing in a lab for cancer. A biopsy is the only sure way to diagnose prostate cancer or know for certain how aggressive it is. Your provider may perform genetic tests on the biopsied tissue. Some cancer cells have characteristics (like mutations) that make them more likely to respond to specific treatments.

Grades and stages of prostate cancer?

Healthcare providers use the Gleason score and cancer staging to determine how serious the cancer is and the types of treatments you need.

Gleason score

The Gleason score allows your provider to rate how abnormal your cancer cells are. The more abnormal cells you have, the higher your Gleason score. The Gleason score allows your provider to determine the grade of your cancer, or its potential to be aggressive.

Staging prostate cancer

Cancer staging allows your provider to determine how advanced your cancer is, or how much it’s spread. Cancer may be in your prostate gland only (local), invading nearby structures (regional) or spread to other organs (metastasized). Prostate cancer most commonly spreads to your bones and lymph nodes. It can also develop in your liver, brain, lungs and other organs.

Treatement of prostate cancer

Your treatment depends on multiple factors, including your overall condition, if the cancer’s spread and how fast it’s spreading. Depending on your treatments, you may work with various healthcare providers, including urologists, radiation oncologists and medical oncologists. Most prostate cancer diagnosed in the early stages can be cured with treatment.

Specific procedures used

Surveillance

Your healthcare provider may monitor your condition instead of providing treatment if your cancer grows slowly and doesn’t spread.

- Active surveillance:You get screenings, scans and biopsies every one to three years to monitor cancer growth. Active surveillance works best if the cancer grows slowly, is only in your prostate and isn’t causing symptoms. If your condition worsens, your provider can start treatments.

- Watchful waiting:Watchful waiting is similar to active surveillance, but it’s more commonly used for people who are frailer with cancer that likely won’t go away with treatment. Also, testing is much less frequent. Instead of eliminating the tumor, treatments usually focus on managing symptoms.

Surgery

A radical prostactomy removes a diseased prostate gland. It can often successfully eliminate prostate cancers that haven’t spread. Your provider can recommend the best removal method if they believe you’d benefit from this surgery.

- Open radical prostatectomy:Your provider makes a single cut (incision) into your abdomen — from your belly button to your pubic bone — and removes your prostate gland. This technique isn’t as common as less-invasive methods like robotic prostatectomy.

- Robotic radical prostatectomy:Robotic radical prostatectomy allows your provider to perform surgery through several tiny incisions. Instead of operating directly, they operate a robot system via a console.

Radiation therapy

You may receive radiation therapy as a standalone treatment for prostate cancer or in combination with other treatments. Radiation can also provide symptom relief.

- Brachytherapy:A form of internal radiation therapy, brachytherapy involves placing radioactive seeds inside your prostate. This approach kills cancer cells while preserving surrounding healthy tissue.

- External beam radiation therapy:With external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), a machine delivers strong X-ray beams directly to the tumor. Specialized forms of EBRT, like IMRT, can direct high doses of radiation toward the tumor while sparing healthy tissue.

Systemic therapies

Your provider may recommend systemic therapies if cancer has spread outside your prostate gland. Systemic therapies send substances throughout your body to destroy cancer cells or prevent their growth.

- Hormone therapy:The hormone testosterone boosts cancer cell growth. Hormone therapy uses medications to combat testosterone’s role in fueling cancer cell growth. The medicines work by preventing testosterone from reaching cancer cells or by reducing your testosterone levels. Alternatively, your provider may recommend surgery to remove your testicles (orchiectomy) so they can no longer make testosterone. This surgery is an option for people who don’t want to take medications.

- Chemotherapy:Chemotherapy uses medicines to destroy cancer cells. You may receive chemotherapy alone or with hormone therapy if your cancer has spread beyond your prostate.

- Immunotherapy:Immunotherapy strengthens your immune system so it’s better able to identify and fight cancer cells. Your healthcare provider may recommend immunotherapy to treat advanced cancer or recurrent cancer (cancer that goes away but then returns).

- Targeted therapy:Targeted therapy zeroes in on the genetic changes (mutations) that turn healthy cells into cancer cells to prevent them from growing and multiplying. Targeted therapies that treat prostate cancer destroy cancer cells with BRCA gene mutations.

Focal therapy

Focal therapy is a newer form of treatment that destroys tumors inside your prostate. Your healthcare provider may recommend this treatment if the cancer is low-risk and hasn’t spread. Many of these treatments are still considered experimental.

- High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU):High-intensity sound waves generate powerful heat to kill cancer cells within your prostate.

- Cryotherapy:Cold gases freeze cancer cells in your prostate, eliminating the tumor.

- Laser ablation:Intense heat directed at the tumor kills cancer cells within your prostate, destroying the tumor.

- Photodynamic therapy:Medications make cancer cells more sensitive to certain wavelengths of light. A healthcare provider exposes cancer cells to these light wavelengths, killing the cancer cells.

Side effects of prostate cancer treatment?

Potential side effects include:

- Incontinence:You may leak urine when you cough or laugh or feel an urgent need to pee even when your bladder isn’t full. This problem usually improves over the first six to 12 months without treatment.

- Erectile dysfunction (ED):Surgery, radiation and other treatments can damage the erectile nerves in your penis and affect your ability to get or maintain an erection. It’s common to regain erectile function within a year or two (sometimes sooner). In the meantime, medications like sildenafil or tadalafil can help by increasing blood flow to your penis.

- Infertility:Treatments can affect your ability to produce or ejaculate sperm, resulting in infertility. If you want children in the future, you can preserve sperm in a sperm bank before starting treatment. After treatments, you may undergo sperm extraction. This procedure involves removing sperm directly from testicular tissue and implanting it into your partner’s uterus.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you’re experiencing treatment side effects. Often, they can recommend medicines and procedures that can help.

Prognosis (outlook) for people with prostate cancer

Your outlook is excellent if your healthcare provider detects prostate cancer early. Almost everyone — 99% — diagnosed with cancer that hasn’t spread outside of their prostate live at least five years after diagnosis.

Prostate cancer survival rates aren’t as good when the cancer’s metastasized, or spread outside of your prostate. Thirty-two percent of people with metastatic prostate cancer are alive five years later.

Blood Cancers

Overview

Blood cancer endangers an essential life force — our blood cells. These cells give us energy, help us fight infection and keep us from bleeding too much. Blood cancer affects how your body produces blood cells and how well those cells work. Fortunately, there are many effective and safe ways to treat blood cancer.

What is blood cancer?

Blood cancer affects how your body produces blood cells and how well those cells work. Most blood cancers start in your bone marrow, the soft, sponge-like material in the center of your bones. Your bone marrow makes stem cells that mature and become red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets.

Normal blood cells fight infection, carry oxygen throughout your body and control bleeding. Blood cancer happens when something disrupts how your body makes blood cells. If you have blood cancer, abnormal blood cells overwhelm normal blood cells, creating a ripple effect of medical conditions. More people are living longer with blood cancer, as healthcare providers find new ways to treat it.

Are blood cancers serious?

Blood cancers are serious illnesses, but other cancer types are more deadly. Blood cancers represent about 10% of all cancers diagnosed and an estimated 3% of all cancer-related deaths. National Cancer Institute data show a steady decline in blood cancer deaths.

Types of blood cancer?

There are three blood cancer types, each with several subtypes. Those cancer types and subtypes are:

- Leukemiais the most common blood cancer in the United States and the most common cancer among children and teenagers. The five-year survival rate has quadrupled over the past 40 years. Types of leukemia include , acute meyeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic meylogenous leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

- Lymphomais cancer of your lymphatic system, which includes your bone marrow. The survival rate has doubled over the past 40 years. Types of lymphoma include Hodgkin lymphoma, non- Hodgkin lymphoma, Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, follicular lymphoma, B-cell lymphoma and Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

- Myeloma is cancer that starts in your bone marrow and affects your plasma cells. Multiple myeloma is the most common myeloma type. More than half of people diagnosed with myeloma are alive five years after diagnosis. Other types of myeloma include plasmavytoma and amyloidis.

What causes blood cancer?

Researchers know blood cancer happens when blood cell DNA changes or mutates, but they aren’t sure why this happens. Your DNA tells cells what to do. In blood cancer, DNA tells blood cells when to grow, when to divide or multiply and/or when to die.

When DNA gives your cells new instructions, your body develops abnormal blood cells that grow and multiply faster than normal and sometimes live longer than normal. When that happens, normal blood cells become lost in an ever-growing horde of abnormal cells that crowd your normal cells and monopolize space in your bone marrow.

Eventually, your bone marrow produces fewer normal cells. That means there aren’t enough normal cells available to do their essential tasks: carrying oxygen through your body, fighting infection and controlling bleeding. Here’s how genetic change may cause the three blood cancer types:

- Leukemia: Researchers think leukemia happens when a combination of environmental and genetic factors triggers DNA changes. In this case, researchers think changes in chromosomes may trigger DNA changes. Chromosomes are strands of DNA. When cells divide and make two new cells, they copy these DNA strands. Sometimes, genes from one chromosome switch to another chromosome. In leukemia, this switch may affect a set of genes that help cells grow and another set of genes that suppress tumors. Researchers believe exposure to high levels of radiation or certain chemicals plays a role in the genetic changes that cause leukemia.

- Lymphoma: Lymphoma happens when there’s a change in genes in white blood cells, called lymphocytes, that causes them to multiply uncontrollably. In addition, abnormal lymphocytes don’t die when normal lymphocytes die. Again, researchers don’t know what triggers the genetic change, but research shows certain infections or having a depressed immune system may be factors.

- Myeloma: In this case, plasma cells in your bone marrow get new genetic instructions that make them multiply. Researchers are investigating potential links between myeloma and chromosomal change that affect genes that control plasma cell growth.

Symptoms of blood cancer

Blood cancer symptoms vary based on blood cancer type, but there some symptoms all three have in common:

- Fatigue: This is feeling so tired you can’t manage your daily activities. You may also feel weak.

- Persistent fever: A fever is a sign your body is fighting infection or responding to abnormal cancer cells.

- Drenching night sweats: This is sweating that comes on suddenly while you’re sleeping, disturbing your sleep and drenching your bedding and clothes.

- Unusual bleeding or bruising: Everyone has bumps, bruises and injuries that make us bleed. Unusual bleeding or bruising is bleeding that doesn’t stop and bruises that don’t heal after two weeks.

- Unexpected or unexplained weight loss: Unexpected weight loss of 10 pounds over a six- to 12-month period is considered unexplained weight loss.

- Frequent infections: Frequent infections may be a sign something is affecting your immune system.

- Swollen lymph nodes or an enlarged liver or spleen: These symptoms may be signs of leukemia or lymphoma.

- Bone pain: Myeloma and leukemia may cause bone pain or tender spots on your bones.

Many blood cancer symptoms are similar to other less serious illnesses’ symptoms. Having any of these symptoms doesn’t mean you have blood cancer. But you should contact your healthcare provider when you notice symptoms or changes in your body that last more than a few weeks.

Diagnose blood cancer

Healthcare providers may begin diagnosis by asking about your symptoms and your medical history. They’ll do complete physical examinations. They may order several kinds of blood and imaging tests, too. The tests they’ll use may be different for each suspected blood cancer type. Tests used to diagnose blood cancer include:

- Complete blood count (CBC):This test measures and counts your blood cells. For example, if your healthcare provider suspects you have leukemia, they’ll look for high (or low) white blood cell counts and lower than normal red blood cell and platelet counts.

- Blood chemistry test: This test measures chemicals and other substances in your blood. In some cases, your healthcare provider may order specific blood test for cancer to learn more about your situation.

- Comutarised tomography (CT) scan: : This test uses a series of X-rays and a computer to create three-dimensional images of your soft tissues and bones. If your healthcare provider suspects you have myeloma, they may order a CT scan to look for bone damage.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan: Your healthcare provider may order an MRI to look for signs of leukemia or lymphoma complications affecting your spine.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan: This test produces images of your organs and tissues at work. Your healthcare provider may order a PET scan to look for signs of myeloma.

- Bone marrow biopsies: Healthcare providers may do bone marrow biopsies to analyze the percentage of normal and abnormal blood cells in your bone marrow. They may also test your bone marrow sample for changes in your DNA that may drive cancer growth.

- Blood cell examination: Healthcare providers may take blood samples so they can examine them under a microscope to look for changes in blood cell appearance. For example, they might order peripheral smear test to look for signs of leukemia or lymphoma.

Treatment of blood cancers

Blood cancer treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. Some blood cancer types respond well to specific treatments. Some blood cancer treatments have significant side effects. Healthcare providers consider factors, including your age, your overall health, the kind of blood cancer you have and specific treatment side effects, before recommending a treatment plan. Some common treatments for blood cancer include:

- Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy is a primary blood cancer treatment, killing cancer cells to either slow down the disease’s progress or eliminate the cancer. Healthcare providers use different drug types for different blood cancers.

- Radiation therapy: Healthcare providers may use radiation to treat leukemia, lymphoma or myeloma. Radiation targets abnormal cells, damaging their DNA so they can’t reproduce. Healthcare providers often combine radiation therapy with other treatments. They may use radiation to ease some symptoms.

- Immunotherapy: This treatment uses your immune system to fight cancer. Immunotherapy may help your body make more immune cells or help your existing immune cells find and kill cancer cells.

- Targeted therpy:This cancer treatment targets genetic changes or mutations that turn healthy cells into abnormal cells.

- CAR T-cell therapy: In CAR T-cell therapy, healthcare providers turn T-cell lymphocytes — a type of white blood cell — into more effective cancer treatment. Healthcare providers may use CAR T-cell therapy to treat B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, multiple myeloma and several types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma if other treatments haven’t worked.

- Atologous stem cell transplsnt: Healthcare providers can collect and store bone marrow stem cells before administering high doses of chemotherapy. Once chemotherapy is done, they’ll replace the protected stem cells. This way, people having autologous stem cell implants can avoid chemotherapy side effects.

- Allogeneic stem cell transplsnt: Sometimes, damaged bone marrow needs to be replaced with healthy bone marrow. Healthcare providers identify a suitable bone marrow donor and use the donor’s cells to replace your damaged ones. This is an effective but dangerous procedure.

How can I reduce risk for developing blood cancer?

Blood cancer happens when blood cell DNA changes or mutates. Researchers don’t know why this happens, which makes it hard to single out specific steps someone could take to reduce their risk. But researchers have identified some factors that appear to play to a role in the genetic change:

- Radiation exposure.

- Certain chemicals.

- Lowered immunity due to infections.

- Family history of blood cancer.

- Inherited conditions that increase the risk of developing blood cancer.

Can blood cancer be cured?

Yes. Often, the goal of blood cancer treatment is curing the condition. But when a cure isn’t possible, there are a growing number of treatments that may put some blood cancers into remission. Remission means the treatment eliminates cancer signs and symptoms for a long time.

Skin cancer

Overview

Skin cancer happens when something changes how your skin cells grow, like exposure to ultraviolet light. Symptoms include new bumps or patches on your skin, or changes in the size, shape or color of skin growths. Most skin cancer is treatable if it’s caught early. Treatments include Mohs surgery, cryotherapy, chemotherapy and radiation.

What is skin cancer?

Skin cancer is a disease that involves the growth of abnormal cells in your skin tissues. Normally, as skin cells grow old and die, new cells form to replace them. When this process doesn’t work as it should — like after exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light from the sun — cells grow more quickly. These cells may be noncancerous (benign), which don’t spread or cause harm. Or they may be cancerous.

Skin cancer can spread to nearby tissue or other areas in your body if it’s not caught early. Fortunately, if skin cancer is identified and treated in early stages, most are cured. So, it’s important to talk with your healthcare provider if you think you have any signs of skin cancer.

Types of skin cancer

There are three main types of skin cancer:

- Basal cell carcinoma, which forms in your basal cells in the lower part of your epidermis (the outside layer of your skin).

- Squamous cell carcinoma, which forms in your squamous cells in the outside layer of your skin.

- Melanoma, which forms in cells called melanocytes. Melanocytes produce melanin, a brown pigment that gives your skin its color and protects against some of the sun’s damaging UV rays. This is the most serious type of skin cancer because it can spread to other areas of your body.

Other types of skin cancer include:

- Kaposi sarcoma.

- Merkel cell carcinoma.

- Sebaceous gland carcinoma.

- Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

Signs and symptoms of skin cancer

The most common warning sign of skin cancer is a change on your skin — typically a new growth or a change in an existing growth or mole. Skin cancer symptoms include:

- A new mole, or a mole that changes in size, shape or color, or that bleeds.

- A pearly or waxy bump on your face, ears or neck.

- A flat, pink/red- or brown-colored patch or bump.

- Areas on your skin that look like scars.

- Sores that look crusty, have a depression in the middle or bleed often.

- A wound or sore that won’t heal, or that heals but comes back again.

- A rough, scaly lesion that might itch, bleed and become crusty.

What does skin cancer look like?

Skin cancer looks different depending on what type of skin cancer you have. Thinking of the ABCDE rule tells you what signs to watch for:

- Asymmetry: Irregular shape.

- Border: Blurry or irregularly shaped edges.

- Color: Mole with more than one color.

- Diameter: Larger than a pencil eraser (6 millimeters).

- Evolution: Enlarging, changing in shape, color or size.

If you’re worried about a mole or another skin lesion, make an appointment and show it to your healthcare provider. They’ll check your skin and may ask you to see a dermatologist and have the lesion further evaluated.

What causes the condition?

The main cause of skin cancer is overexposure to sunlight, especially when you have sunburn and blistering. UV rays from the sun damage DNA in your skin, causing abnormal cells to form. These abnormal cells rapidly divide in a disorganized way, forming a mass of cancer cells.

Risk factors for skin cancer

Anyone can get skin cancer, regardless of race or sex. But some groups get it more than others. Before the age of 50, skin cancer is more common in women and people assigned female at birth (AFAB). After 50, though, it’s more common in men and people assigned male at birth (AMAB). And it’s about 30 times more common in non-Hispanic white people than non-Hispanic Black people or people of Asian/Pacific Islander descent. Unfortunately, skin cancer is often diagnosed in later stages for people with darker skin tones. This makes it more difficult to treat.

Although anyone can develop skin cancer, you’re at increased risk if you:

- Spend a considerable amount of time working or playing in the sun.

- Get easily sunburned or have a history of sunburns.

- Live in a sunny or high-altitude climate.

- Tan or use tanning beds.

- Have light-colored eyes, blond or red hair and fair or freckled skin.

- Have many moles or irregularly shaped moles.

- Have actinic keratosis (precancerous skin growths that are rough, scaly, dark pink-to-brown patches).

- Have a family history of skin cancer.

- Have had an organ transplant.

- Take medications that suppress or weaken your immune system.

- Have been exposed to UV light therapy for treating skin conditions such as eczema or psoriasis.

Diagnosed of skin cancer

First, a dermatologist may ask you if you’ve noticed changes in any existing moles, freckles or other skin spots, or if you’ve noticed any new skin growths. Next, they’ll examine all of your skin, including your scalp, ears, palms of your hands, soles of your feet, between your toes, around your genitals and between your buttocks.

Stages of skin cancer

Cancer stages tell you how much cancer is in your body. The stages of skin cancer range from stage 0 to stage IV. In general, the higher the number, the more cancer has spread and the harder it is to treat. But the staging for melanoma is different from non-melanoma skin cancers that start in your basal or squamous cells.

Melanoma staging

- Stage 0 (melanoma in situ):The melanoma is only in the top layer of your skin.

- Stage I: The melanoma is low risk and there’s no evidence that it has spread. It’s generally curable with surgery.

- Stage II:It has some features that indicate that it’s likely to come back (recur), but there’s no evidence of spread.

- Stage III: The melanoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes or nearby skin.

- Stage IV:The melanoma has spread to more distant lymph nodes or skin, or has spread to internal organs.

Non-melanoma staging

- Stage 0:Cancer is only in the top layer of your skin.

- Stage I (1):Cancer is in the top and middle layers of your skin.

- Stage II (2):Cancer is in the top and middle layers of your skin and moves to target your nerves or deeper layers of skin.

- Stage III (3): Cancer has spread beyond your skin to your lymph nodes.

- Stage IIIV (4):Cancer has spread to other parts of your body and your organs like your liver, lungs or brain.

Treatement of skin cancer

Treatment depends on the stage of cancer. Sometimes, a biopsy alone can remove all the cancer tissue if it’s small and limited to the surface of your skin. Other common skin cancer treatments, used alone or in combination, include:

- Cryotherapy:Your dermatologist uses liquid nitrogen to freeze skin cancer. The dead cells slough off after treatment.

- Excisional surgery:Your dermatologist removes the tumor and some surrounding healthy skin to be sure all the cancer is gone.

- Mohs surgery:Your dermatologist removes only diseased tissue, saving as much surrounding normal tissue as possible. Providers use this to treat basal cell and squamous cell cancers and, sometimes, other skin cancers that develop near sensitive or cosmetically important areas, like your eyelids, ears, lips, forehead, scalp, fingers or genital area.

- Curettage and electrodesiccation: Your dermatologist uses an instrument with a sharp, looped edge to remove cancer cells as it scrapes across the tumor. Then, they use an electric needle to destroy any remaining cancer cells. Providers often use this to treat basal cell and squamous cell cancers and precancerous skin tumors.

- Chemotherapy:Your dermatologist or oncologist uses medications to kill cancer cells. Anticancer medications can be applied directly on the skin (topical chemotherapy) if limited to your skin’s top layer or provided through pills or an IV if the cancer has spread to other parts of your body.

- Immunotherapy:Your oncologist gives you medications to train your immune system to kill cancer cells.

- Radiation therapy:Your radiation oncologist uses radiation (strong beams of energy) to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing and dividing.

- Photodynamic therapy:Your dermatologist coats your skin with medication, which they activate with a blue or red fluorescent light. This therapy destroys precancerous cells while leaving normal cells alone.

Can skin cancer be prevented?

In most cases, skin cancer can be prevented. The best way to protect yourself is to avoid too much sunlight and sunburns. UV rays from the sun damage your skin, and over time, this may lead to skin cancer.

Ways to protect yourself from skin cancer include:

- Use a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a skin protection factor (SPF) of 30 or higher. Broad-spectrum sunscreens protect against both UV-B and UV-A rays. Apply the sunscreen 30 minutes before you go outside. Wear sunscreen every day, even on cloudy days and during the winter months.

- Wear hats with wide brims to protect your face and ears.

- Wear long-sleeved shirts and pants to protect your arms and legs. Look for clothing with an ultraviolet protection factor label for extra protection.

- Wear sunglasses to protect your eyes. Look for glasses that block both UV-B and UV-A rays.

- Use a lip balm with sunscreen.

- Avoid the sun between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.

- Avoid tanning beds. If you want a tanned look, use a spray-on tanning product.

- Ask your healthcare provider or pharmacist if any of the medications you take make your skin more sensitive to sunlight. Some medications known to make your skin more sensitive to the sun include tetracycline and fluoroquinolone antibiotics, tricyclic antibiotics, the antifungal agent griseofulvin and statin cholesterol-lowering drugs.

- Regularly check all your skin for any changes in size, shape or color of skin growths or the development of new skin spots. Don’t forget to check your scalp, ears, the palms of your hands, soles of your feet, between your toes, your genital area and between your buttocks. Use mirrors and even take pictures to help identify changes in your skin over time. Make an appointment for a full-body skin exam with your dermatologist if you notice any changes in a mole or other skin spot.

What is the outlook for people with skin cancer?

Nearly all skin cancers can be cured if they’re treated before they have a chance to spread. The earlier skin cancer is found and removed, the better your chance for a full recovery. It’s important to continue following up with your dermatologist to make sure cancer doesn’t come back. If something seems wrong, call your doctor right away.

Most skin cancer deaths are from melanoma. If you’re diagnosed with melanoma:

- The five-year survival rate is 99% if it’s detected before it spreads to your lymph nodes.

- The five-year survival rate is 66% if it has spread to nearby lymph nodes.

- The five-year survival rate is 27% if it has spread to distant lymph nodes and other organs.

Brain Cancer (Brain Tumor)

Overview

Brain tumors can be malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous) and can affect children and adults. But whether they’re cancerous or not, brain tumors can impact your brain function if they grow large enough to press on surrounding tissues. There are several treatment options for brain tumors.

What is a brain tumor?

A brain tumor is an abnormal growth or mass of cells in or around your brain. Together, spinal tumors and brain tumors are called central nervous system (CNS) tumors.

Brain tumors can be malignant (cancerous) or benign (noncancerous). Some tumors grow quickly, while others are slow growing.

Only about one-third of brain tumors are cancerous. But whether they’re cancerous or not, brain tumors can impact brain function and your health if they grow large enough to press on surrounding nerves, blood vessels and tissue.

Tumors that develop in your brain are called primary tumors. Tumors that spread to your brain after forming in a different part of your body are called secondary tumors, or metastatic brain tumors. This article focuses on primary brain tumors.

Types of brain tumors

Researchers have identified more than 150 different brain tumors.

Healthcare providers categorize primary tumors as glial (composed of glial cells in your brain) or non-glial (developed on or in the structures of your brain, including nerves, blood vessels and glands) and benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Many types of brain tumors can also form in your spinal cord or column.

Usually benign brain tumors

Types of brain tumors that are usually benign include:

- Chordomas: These slow-growing tumors typically begin at the base of your skull and the bottom part of your spine. They’re mostly benign.

- Craniopharyngiomas: These tumors usually arise from a portion of your pituitary gland. They’re difficult tumors to remove because of their location near critical structures deep in your brain.

- Gangliocytomas, gangliomas and anaplastic gangliogliomas: These are rare tumors that form in neurons (nerve cells).

- Glomus jugulare: These tumors are typically located just under the base of your skull at the top of your jugular vein (neck vein). They’re the most common form of glomus tumor.

- Meningiomas:These are the most common type of primary brain tumors. Meningiomas typically develop slowly. They form in the meninges, the layers of tissue that protect your brain and spinal cord. In rare cases, a meningioma can be malignant.

- Pineocytomas: These slow-growing tumors form in your pineal gland, which is located deep in your brain and secretes the hormone melatonin.

- Pituitary adenomas: These tumors form in your pituitary gland, which is located at the base of your brain. Your pituitary gland makes and controls hormones in your body. Pituitary adenomas are usually slow growing and they may release excess pituitary hormones.

- Schwannomas: These are common benign brain tumors in adults. They develop from the Schwann cells in your peripheral nervous system or cranial nerves. Schwann cells assist the conduction of nerve impulses. Acoustic neuromas are the most common schwannoma. These tumors occur on your vestibular nerve (the nerve that leads from your inner ear to your brain).

Types of brain tumors

Researchers have identified more than 150 different brain tumors.

Healthcare providers categorize primary tumors as glial (composed of glial cells in your brain) or non-glial (developed on or in the structures of your brain, including nerves, blood vessels and glands) and benign (noncancerous) or malignant (cancerous).

Many types of brain tumors can also form in your spinal cord or column.

Usually benign brain tumors

Types of brain tumors that are usually benign include:

- Chordomas: These slow-growing tumors typically begin at the base of your skull and the bottom part of your spine. They’re mostly benign.

- Craniopharyngiomas: These tumors usually arise from a portion of your pituitary gland. They’re difficult tumors to remove because of their location near critical structures deep in your brain.

- Gangliocytomas, gangliomas and anaplastic gangliogliomas: These are rare tumors that form in neurons (nerve cells).

- Glomus jugulare: These tumors are typically located just under the base of your skull at the top of your jugular vein (neck vein). They’re the most common form of glomus tumor.

- Meningiomas:These are the most common type of primary brain tumors. Meningiomas typically develop slowly. They form in the meninges, the layers of tissue that protect your brain and spinal cord. In rare cases, a meningioma can be malignant.

- Pineocytomas: These slow-growing tumors form in your pineal gland, which is located deep in your brain and secretes the hormone melatonin.

- Pituitary adenomas: These tumors form in your pituitary gland, which is located at the base of your brain. Your pituitary gland makes and controls hormones in your body. Pituitary adenomas are usually slow growing and they may release excess pituitary hormones.

- Schwannomas: These are common benign brain tumors in adults. They develop from the Schwann cells in your peripheral nervous system or cranial nerves. Schwann cells assist the conduction of nerve impulses. Acoustic neuromas are the most common schwannoma. These tumors occur on your vestibular nerve (the nerve that leads from your inner ear to your brain).

- Schwannomas: These are common benign brain tumors in adults. They develop from the Schwann cells in your peripheral nervous system or cranial nerves. Schwann cells assist the conduction of nerve impulses. Acoustic neuromas are the most common schwannoma. These tumors occur on your vestibular nerve (the nerve that leads from your inner ear to your brain).

Cancerous (malignant) brain tumors

Approximately 78% of cancerous primary brain tumors are gliomas. These tumors develop in glial cells, which surround and assist nerve cells. Types of gliomas include:

- Astrocytoma:These tumors are the most common type of glioma. They form in the star-shaped glial cells called astrocytes. They can form in many parts of your brain, but most commonly occur in your cerebrum.

- Ependymomas: These tumors often occur near the ventricles in your brain. Ependymomas develop from ependymal cells (called radial glial cells).

- Glioblastoma (GBM): These tumors form in glial cells called astrocytes. GBMs are the fastest-growing astrocytoma.

- Oligodendroglioma: These uncommon tumors begin in cells that create myelin (a layer of insulation around nerves in your brain).

Medulloblastoma is another type of cancerous brain tumor. These tumors are fast growing and form at the base of your skull. They’re the most common cancerous brain tumor in children.

Who do brain tumors affect?

Brain tumors affect children and adults and can develop at any age. They’re slightly more common in people assigned male at birth (AMAB) than people assigned female at birth (AFAB).

Meningioma, which is usually benign, is the only type of brain tumor that’s more common in people AFAB.

The most serious type of brain tumor, glioblastoma, is becoming more common among people who are as the general population ages.

How serious are brain tumors?

Brain tumors — whether cancerous or not — can cause serious problems. This is because your skull is rigid and doesn’t provide room for the tumor to expand. Also, if a tumor develops near parts of your brain that control vital functions, it may cause symptoms, such as:

- Weakness

- Difficulty walking.

- Problems with balance.

- Partial or complete loss of vision.

- Difficulty understanding or using language.

- Memory issues.

Brain tumors can cause problems by:

- Directly invading and destroying healthy brain tissue.

- Putting pressure on nearby tissue.

- Increasing pressure within your skull (intracranial pressure).

- Causing fluid to build up in your brain.

- Blocking the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) through the spaces within your brain, causing those spaces to enlarge.

- Causing bleeding in your brain.

However, some people have brain tumors that never cause symptoms or grow large enough to compress surrounding tissues.

Signs and symptoms of brain tumors

Some people who have a brain tumor experience no symptoms, especially if it’s very small.

Signs and symptoms of a brain tumor vary depending on the tumor’s location, size and type. They can include: